By Drew Bush

More than 1,450 individuals collectively generated 2,010 ideas, comments and questions for the Canadian Government on its Action Plan for Open Government 2.0. But one researcher with The Programmable City project who studies open data and open government in Canada feels these numbers miss the real story.

The process leading up to the “What We Heard” report, issued after the completion of consultations from April 24–October 20, 2014, only reflected the enthusiasm of the open data programming community, she says. A broader engagement with civil society organizations that most need help from the government to accomplish their work was severely lacking.

“They might be really good at making an app and taking near real time transit data and coming up with a beautiful app with a fantastic algorithm that will tell you within the millisecond how fast the bus is coming,” Tracy Lauriault, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis (NIRSA), said. “But those aren’t the same people who will sit at a transit committee meeting.”

She believes the government has failed to continue to include important civil society groups in discussions of the plan. Those left out have included community-based organizations, cities having urban planning debates, anti-poverty groups, transportation planning boards and environmental groups. She’s personally tried to include organizations such as the Canadian Council on Social Development or the Federation of Canadian Municipalities only to have their opinions become lost in the process.

“There is I think a sincere wish to collect information from the people who attend but then that’s it,” she said. “There is no follow up with some people or the comments that are made—or even an assessment, a careful assessment, of who’s in the room and what they’re saying.”

“I’m generally disappointed in what I see in most of these documents,” she added. “When they were delivering or working towards open data back in 2004, 2005 it was really about democratic deliberation and evidenced-informed decision-making—making sure citizens and civil society groups could debate on par with the same types of resources government officials had.”

For it’s part, the government notes that 18 percent of the participants came from civil society groups. But such groups were really just ad-hoc groups who advocate for data or are otherwise involved in aspects of new technology, according to Lauriault. Such input, while useful, is usually limited to requests on datasets, ranking what kind of dataset you’d like to see or choosing what platforms to use to view it, she added.

The report itself notes comments came from the Advisory Panel on Open Government, online forums, in-person sessions, email submissions, Twitter (hash tag #OGAP2), and LinkedIn. In general, participants requested quicker, easier, and more meaningful access to their government, and a desire to be involved in government decision making beyond consultations.

Some suggested that the Government of Canada could go even further toward improving transparency in the extractives sector. For example, proposed legislation to establish mandatory reporting standards could stipulate that extractives data be disclosed in open, machine-readable formats based on a standard template with uniform definitions.

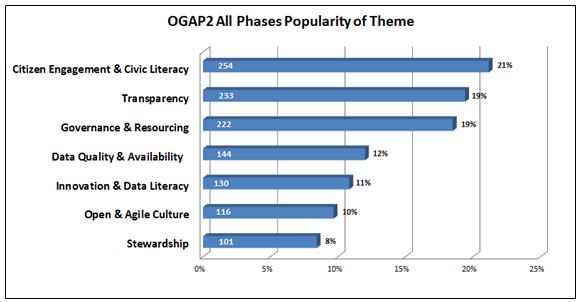

Major themes to emerge from citizen comments on the “What We Heard Report” (Image courtesy of the Government of Canada).

Find out more about this figure or the “What We Heard” report here.

If you have thoughts or questions about the article, get in touch with Drew Bush, Geothink’s digital journalist, at drew.bush@mail.mcgill.ca.